VOCAL RECORDING – PREPARATION

I know this is not directly related to mixing, but a great vocal performance and recording is the best foundation for a quality vocal in the mix – so if you’re in charge of vocal production, here are some ideas for you. Getting this right can save you a lot of work in the mix!

1. GET THE SINGER TO DO A VOCAL WARM-UP

There are some great vocal warm-up programs out there. Just do a search on YouTube for “vocal warm up” and you’ll find lots of options. The warm up should take at least 30 minutes, a full hour is even better. A good warm up has a slow build, and consists of a big variety of notes, expressions and phrases. Trust me, it’s worth it and will save you hours in vocal recording. It’s basically like sports – no professional athlete would ever skip preparation and warm up! My favorite vocal warm up is by Stevie Lange – on her website you can find female and male versions.

2. GET THE SINGER TO DRINK LOTS OF STILL WATER

In addition to the warm up, the singer should drink lots of still water before and also during the session.

3. PRINT OUT THE LYRICS

This will be helpful for both the producer and the singer. Type down the lyrics of the song and print 2 copies, one for you, one for the singer. Make sure the font is large enough so it’s easy to read. Print it on two pages if it doesn’t fit on one. Have a music stand and a working pen ready for the singer and also yourself, so you can both make notes. Place the music stand and note sheet in a way that it doesn’t reflect back into the microphone – the right angle helps wonders!

4. RECORD A COUPLE OF RUNS THROUGH THE ENTIRE SONG

I know – recording vocals in sections is very popular, but it’s still a good idea to record the entire song from start to finish at the beginning of the session. Mainly because it gives you a better idea of the macro dynamics of the song. When recording a song in sections, you can easily overpower the first verse, then realize the singer can’t top the power in the chorus. So make sure to define the tone and power of each section during these run-throughs.

5. RECORD THE SONG IN SECTIONS

If the complete runs went very well, this is just a backup, but the reality is that most vocals are recorded in sections. Loop a song part (e.g. verse or chorus), make sure to have 2 – 4 bars pre-roll of just music between every take and just keep recording. You will probably see the performance improvewith every new take until at one point the quality drops which is when you should stop and go to the next section. Once you went through all the sections, you should start at the first section again because there was likely a development in quality, and this second session is usually a huge improvement over the first one.

6. HOW MANY TAKES?

The number of takes you want to capture varies – there is no rule to that. I’ve worked with professional session singers in New York that were so well prepared that 3 takes was all I’ve ever needed. In the 2000s, I’ve worked with a lot of young and inexperienced casting TV show artists (Idol, X-Factor, The Voice), where I would record a minimum of 10 – 20 takes of each section. You have to decide it from case to case, but keep in mind that sometimes, this one vocal session is your only chance to get it right, and better be safe than sorry!

VOCAL RECORDING WHAT TO AVOID

Now on to the more technical aspects of vocal recording – here are some of the biggest issues I see:

1. TOO MUCH TREBLE AND “ESSES”

Vocal sounds are a matter of trends. For years, the Sony C800G tube microphone has been very popular due to its emphasis and fine resolution on higher frequencies. Without a doubt, one of the best mics ever made, but at the same time, depending on the type of vocal, there might be excessive sibilance on the vocal-tracks. A mic that emphasizes the highs is not the main source of trouble here – its excessive sibilance pushed into a tracking compressor that creates the problem. For this reason, I don’t recommend a tracking compressor when trying to achieve a vocal sound with crisp highs. Along with more organic productions, recent years brought back more natural, organic-sounding vocals, with less emphasis on the highs. Another positive development for music producers is that the market for affordable studio mics is growing and changing. Classic microphone designs are getting very affordable, costing a fraction of the price of 10 years ago, and the latest trend of DSP-modeled microphones is already giving us a glimpse into the future.

2. NO POP SHIELD

If you don’t use a pop shield in front of your vocal mic, chances are you will literally have dropouts in your audio signal. Not every pop shield sounds the same – it’s definitely worth having a few different ones at hand and listen to the difference.

3. RECORDING IN A VOCAL BOOTH

Most small home-made vocal booths are not properly absorbing (= reducing reverb-time of the room) the sound across the entire frequency spectrum. All they do is dampening the highs, leaving you not only with a boomy sound, but also with comb-filtering that results in resonances across the mids. Vocals sound better recorded in larger rooms, and it is a lot easier to deal with a few more reflections from a large room than removing resonances from comb-filtering. Of course, an ideal environment is spacey (= lots of space between the singer and the next hard wall) and absorbing at the same time. If you have an acoustically treated control room, try recording the vocals there. Movable acoustic panels (aka GOBOs) can be very helpful as well. I usually record vocals in my large control room while putting the GIK Acoustic PIB (Portable Isolation Booth) around the back of the microphone.

Again, if in doubt, don’t use a tracking compressor – it’s a habit from the analog tape tracking age, where high recording levels where the treat against the ever existing noise floor of tape. In a digital 24bit world, set your mic- pre and tracking levels carefully, and make sure you have plenty of headroom even during the loudest vocal parts of the song. A high quality mic pre and A/D converter can be a good investment, but to be fair, even lower priced USB audio interfaces provide lots of dynamic in 2019.

VOCAL TUNING

For me, tuning vocals is part of fixing the performance and I’m not a big fan of it as part of the mixing process. It can take a lot of time and attention away from getting the mix right in a macro, but since it’s technically possible, it’s part of our repertoire of tools.

Here are some basics on using tuning plugins in a mix:

1. Basic Setup

Once more, you need to know the key of the song you’re mixing and the exact notes covered by the vocals. Every tuning plugin has a setting for the song-key. Setting the song-key to “chromatic” works in theory, but can create notes that are completely wrong. Also, it’s not enough to set the key to C minor, when both B and Bb are possible notes depending on the context of the chord progression. Then, there’s songs that modulate between different keys, in that case it’s good to have separate vocal tracks for these sections. Once you have set the correct key, the setup is straight forward for most pop-songs or similar genres.

2. Automating Speed / Response Time

Vocal tuning plugins always have a speed-setting that determines the speed in which a note will be tuned. When it’s set fast, you get that classic FX-sound, but when set to a slower value, the tuning plugin can be very subtle as the plugin takes a long time to “bend” the tone to the target note, just like a good singer would do naturally. There’s definitely a setting with a long speed time that makes vocal tuning completely unnoticeable. The next step is to draw the speed in the automation of your DAW. If there’s a note or phrase that needs tuning, you just automate the speed to a faster value. The automation curve you’re using to go from slow to fast is the factor for how much you hear side-effects of tuning. I am of course assuming that you want the vocal to sound natural, with no side-effect. When using tuning plugins, avoid having all doubles of the same vocal-line tuned. Especially on a backing vocal, if you have two doubled takes, only tune one of them. If you have more than two, only tune half of them, and between the tuned ones, fine-tune them against each other (for example: left BV at -5 cent, right BV at +5 cent).

3. Vocal Comping

Another trick that needs to happen at production stage is having the tuning plugin in your monitor chain while comping the vocal takes from your recording session. That way, you can choose to not select takes that have noticeable side-effects /artefacts from the tuning plugin.

BUILDING THE LEAD VOCAL-CHAIN

All of the following, please do at a low listening level. I tend to use my small portable stereo-speakers (aka “kitchen radio”) for that and start by leveling the untreated lead vocal so that it sits a little low in the track, just loud enough so you can understand the lyrics and follow the melody. Let me make an important statement – and I’ll say this a few more times in the book: keep going back between these different building blocks for fine-tuning! Just as an example, you will need to re-adjust the sibilance once you’ve added the final “attitude”- compressor. That goes for each building block. Go back and forth between the building blocks and re-adjust. Also, watch your gain staging – make sure the input level at each building block is similar to the output level. This chain has 3 dynamics processors with EQs in between, they are kind of “sharing” the workload of making the vocal sit tight in the mix. None of these building blocks need to do the “heavy lifting” on their own, each has their own role, and less is more. Bypassing one or more building blocks is always an option. Many times you don’t need all of them! Before I go through the chain, I’d like to again stress the importance of sending the correct level into the plugin chain. Start with an average (RMS)-level of -18dBFS here (that’s the scale in your DAW). If your recording is louder than that, lower it using a gain plugin.

1. CONTINUITY

Starting with the untreated, “naked” lead vocal-track, I want you to first understand the concept of having two types of volume automation on a vocal: before the processing chain, and after it. This first one evens out the performance of the singer. You could say it creates the continuity of levels in the vocal that you wished the singer had delivered in the first place. This is something that overlaps and goes back to mix preparation, and there is a fair chance that this is already in a good place. To confirm this, run the mix, go through the song from start to end and find spots where phrases or syllables of the lead vocals drop in level, or jump out considerably. Correct these phrases in whole dB-values – in other words, don’t go too much into detail, don’t draw complex automation curves etc., this is just one small step to even out the lead vocal across the song. Waves has a plugin called Vocal Rider that can do the job. You can set a target-level for the vocals and depending on the speed-setting (fast or slow) it will keep your levels steady and gets very close to an engineer riding the faders manually. Make sure the output level stays at around -18dBFS – this goes for the output of all plugins in this chain.

2. SIBILANCE

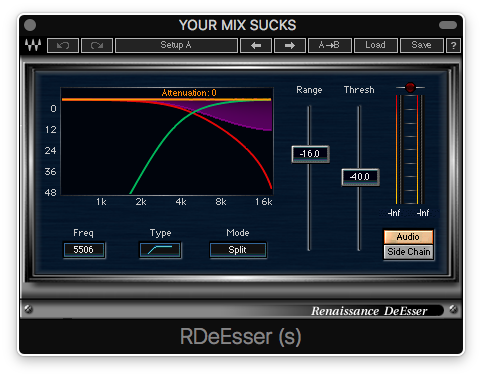

Do you feel the sound of the vocal leans towards too much sibilance? Time to use a De-Esser, which is a specialized compressor that has an EQ in the sidechain. A De-Esser can reduce the level of syllables that have too much treble (typically between 5-12kHz). The frequency that you want to reduce can usually be set in the plugin, as well as the threshold (minimum level at which it starts working) and the amount of reduction in dB. You can use an analyzer to find out at which frequencies the “Esses” are jumping out. Alternatively, reducing the sibilance pre plugin chain is a more precise way to do this. In that case, I isolate the “Esses” to their own regions which I drag to a separate track but same channel strip (so I can select all “Esses” at the same time). I reduce the gain on these regions between 6dB – 10dB, depending on how much the vocal gets compressed in the mix. You want to set them low enough to run below the compressor/s threshold (If this is new to you, we’ll talk about this in chapter 9). If you can’t get a De-Esser to achieve the same – use this technique! You can also completely isolate “Esses” to another channel strip and EQ/compress them differently. Same goes for breathing noises. Waves has developed a total of 3 distinctly different De-Essers over the years, all of which can be useful depending on the situation. The latest Waves Sibilance plugin will cover you in all of these situations. The original Waves DeEsser in “Wide” mode has been my “go to”-plugin for many years when I don’t want the De-Esser to manipulate the sound. In “Wide”- mode, the De-Esser is just reducing the level, every time sibilance is occurring at the selected frequency. It’s very quick and intuitive to dial in, and has a split mode as well which reduces sibilance at just the specific frequencies. The Waves Renaissance DeEsser does a similar thing, but has a slightly different vibe to it – I like the way it smoothens out the sound of the “Esses” in “Split” Mode.

The Waves Sibilance is their latest De-Esser, based on the Waves Organic ReSynthesis engine. It has the most variable and flexible settings including a cross- fader that can mix between wide and split-mode, very variable detection of sibilance and separate controls for threshold and range.

3. WARMTH

With the vocal sitting a little low in the track, we now need to develop a feeling for what’s missing. We do that by adding frequencies using EQs, starting from the low mids.

A. Broad boost between 200Hz and 500Hz

The Waves PuigTec Midrange Equalizer MEQ 5 is usually my first EQ in the vocal chain, but you can simulate these (broad) curves with many other EQs. I don’t ever go lower than 200Hz, and occasionally up to 700Hz. The effect we want to get here is that the vocal gets more weight and warmth in the mix. If the vocal is well tracked, it comes with a lot of that quality in the recording and you may not need to do anything here. This is why people use various transformer or tube-based equipment (from Mics to EQs/Compressors) during tracking. However, a lot of modern vocal recordings sound rather thin, and a nice boost in the low mids can help that! If you like the character you’re adding with the boost, you can even do a little bit too much of it. We can then counterbalance that in the next steps. In case the vocal already sounds overly “muddy” or “boomy”, add an EQ plugin like F6 RTA at the beginning of the plugin chain, locate and remove the frequencies that cause this effect. Watch the interdependence of that – once you’ve removed resonances, you have more leeway to use that broad Pultec-boost again. You really can’t go wrong with a Pultec, but there are of course other EQ emulations that do a similar job. We are looking at more EQ models in chapter 9.

B. Tube compressor for tone

After the boost, insert a compressor for tone – we are not after compression for level automation here, but want to add harmonics on top of the low mid boost and create a sense of glue. The classic Fairchild 660/670 (available by Waves as PuigChild Compressor) works great here, but don’t limit yourself – many compressors can do the job. Just make sure the compression is very subtle. A compressor after an EQ boost works so well because the two components interact. The more you boost a specific frequency, the more compression will be applied to that frequency. So the two balance each other out, which makes that combo very organic. Light tape saturation can also work here – and we are taking a closer look at more classic compressors in a later chapter!

The Waves PuigChild 660 is modeled after a rare Fairchild Compressor (The picture shows the mono version which is called 660, the stereo version is called 670)

4. PRESENCE

In a dense mix, this is were we create the frequencies that make the vocal cut through the rest of the instruments. We can go to extremes here, but before you start playing with the mid boost, set up the “attitude” compressor that follows it right away. It’s needed to tame the mid boosts as they can get very harsh. Often, less or no boosting in the mids is needed in less populated parts of the song, but when the vocals are up against a wall of sound, you will need a musically composed texture of “cut through” frequencies there.

Various boosts between 1kHz and 8kHz (SSL EQ)

This is more complicated to get right, compared to creating warmth. Start with a SSL-type EQ and boost the high shelf at 8kHz +10dB, then pull back again to 0dB and find a great setting for it somewhere in the middle. Try switching between bell and shelf characteristics (bell will just boost around the set frequency, while shelf also includes all frequencies above.) If 8k is boosting sibilance too much, go a tiny bit lower. Continue by using the HMF band to boost at 4k. And the LMF to boost 2kHz. Move these around until you find a good balance – but keep in mind, not boosting anything is always an option. The goal is to create a cluster of mid-boosts that really becomes one colorful and musical texture of mid-boosts between 1kHz and 8kHz. You can achieve good results with stock EQs of your DAW, but there is a reason why SSL EQs are famous for their musicality in the mids. API works as well. Not a job for a Pultec.

5. ATTITUDE

This compressor’s job is to tame the mid-boosts we’ve just created. We want to see it work hard and fast, but it needs to have a lot of musicality to reduce the harshness of the mid boosts. The classic Bluestripe has become my favorite compressor for this stage and the harder you drive it, the more “attitude” you’re getting. Waves has recently introduced the (Chris Lord-Alge, just sayin’) CLA MixHubwhich, luckily, combines both a classic SSL-type EQ and the BlueStripe compressor into one plugin.

6. FINAL TONE AND DYNAMICS CONTROL

A. EQ

A final EQ can round off highs and mids. I like the Waves PuigTec EQP-1A here, to boost at 20Hz, and attenuate at 20kHz. This plugin is modeled after the legendary 1950s Pultec EQP-1 tube equalizer. Your vocals will sound more analog when you roll off the top end slightly. Both the boost at 20Hz, and the attenuation at 20kHz should not affect the essence of the tone you have created. The boosts can add little bit of weight, and the cut removes top end energy that only hurts at loud volumes.

B. Brickwall Limiter

You can use a limiter at the end of the chain to catch occasional peaks that jump out. Only catch occasional peaks, and set the release time higher than 100ms. A digital brickwall limiter works well here. I happen to be a fan of the classic Waves L1 in this place.

PLEASE KEEP IN MIND!

The plugin chain outlined above is pretty complex. There is of course the possibility of processing the vocals too much with a signal chain like this. When you want a really natural vocal sound, you might just need 3B (the subtle tube compressor) and 6A (Pultec for basic tone control). A natural vocal sound requires a very good recording though, and we rarely have an influence on that as mix engineers. On the other hand, this plugin chain is designed to be able to deal with any type of vocal, and when the vocal needs to cut through a dense mix, processing is absolutely necessary. However, subtle settings in each plugin can still cumulate in a drastic overall effect, while retaining a natural tone.

If you found this post helpful, check out the YOUR MIX SUCKS Waves Edition. YOUR MIX SUCKS is the complete methodology for the entire mixing process from preparation to delivery. In addition to the technical and artistical side of things, the e-book also deals with the people aspects of mixing audio: From networking to dealing with client feedback. Over the course of 14 chapters the Waves Edition is the ultimate guide and inspiration to mixing music with Waves plugins.