GAIN STAGING

Exactly how people feel about their gain structure in mixing – « Gain Staging » being the strategy you chose to use your bank account of dBs, if you even have a strategy….And this is what we need to talk about! Like your bank account, the gain structure of your mix needs enough headroom to be able to deal with crazy or unexpected events. Just imagine you’re happy with the mix and the artist or producer walks in and says: « Dude, we need the kick louder in the mix. A lot louder! » OK, you start turning the kick up, and by the time it’s where you need it, the drum-levels are up 6dB – hitting digital red on the mix bus!

Just before digital audio took over as a recording standard, early DAW manufacturers in the 1990s made ahistoric mistake in laying out the wrong scales for digital level meters: no warning all the way up until 0dB, so you wouldn’t know you’re in trouble until it’s too late.

Whereas 0dBVU in analog (on a VU meter) used to be a reference point for solid levels, early DAWs used 0dBFS (FS for « full scale ») as the « point of no return » Digital tape recorders from Sony and Studer (DASH- machines) did a lot better, but they were six-figure digital multitrack-recorders that were the industry- standard before DAWs. Fast forward – DAWs took over between 1991 and 1998 – Digidesign ProTools being the first and most popular one, others like Cubase and Logic followed by extending their MIDI-based sequencers with « audio »-features. What all of them should have done from the beginning is:

- Make -18dBFS = 0dBVU, as this is an appropriate translation of what happens once the audio leaves the D/A-converter

- Declare levels higher than -18dBFS as as « yellow zone »

- Declare -8dBFS as « red zone »

By setting the 0dB-reference to digital « red », DAWdesigners made a historic mistake that affects the quality of mixes to this day. Prior to digital audio, people were not leaving a lot of headroom in analog as it would bring up noise, and driving a signal hard to tape even had pleasant side-effects for certain types of music (tape compression, soft-clipping transients, added harmonics). Early digital audio was at 16bit resolution (in theory 96dB of dynamics), and coming straight out of the analog world, people still felt it wasn’t clever to leave extra headroom. They were partly right, as the combined dynamics of 16bit and early converter designs were barely reaching 90dB, best case. At the same time, pushing the limits of these converter designs to the last dB wasn’t the best decision either. From the early 2000s on though, the processing of all DAWs was operating at a minimum of 24bit resolution, which means you have 144dB of dynamic at hand at any time. 144dB of dynamic at hand, and people complain about not having enough headroom!

That of course exceeds what analog circuits are capable of reproducing. Even the best OP-Amps used in AD/ DA-convertors can only go as far as 125dB (e.g. the LME49720, sidenote for analog circuit developers), so we can plan with as much headroom as we like, it won’t affect the quality of the audio. To cut a long story short – here’s what you do:

GUIDE TO SOLID GAIN STAGING

Stage 1: Tracking

When you’re tracking vocals or instruments,

• keep average levels around -15dB to -18dB

• peaks shouldn’t go higher than -8dB to -5dB

Stage 2: Your individual tracks

Most individual tracks people send me for mixing are too loud – once I start summing them, I’m at least 6dB into the digital red. I do not compensate for that with gain reduction on my master or summing bus, and I also do not lower the individual channel faders! With the channel fader set to unity gain (= 0dB), each single element needs to have a solid headroom of about 12dBFS to 18dBFS. I recommend putting a simple gain plugin in the second slot of your plugin chain (always leave the first slot free in the case you want to insert a test tone-oscillator to check your processing chain on an analyzer). Producers usually send me their individual tracks pretty hot, with peaks close to 0dB, and I have made it a habit to put a gain plugin across every individual track that reduces levels by 15dB (set to -15dB). That ensures lots of headroom in the master- bus when mixing/summing the individual signals. Most DAWs have a simple gain or « trimmer »-plugin. In Cubase, there is a pre-gain within the « Channel Strip » that will do the job.

Stage 3: Your Mix Bus

The mix bus is where your bus compressor (if you’re using one) is inserted, and it can have other processors, from EQs to subtle Tape Compression, etc. (which is not the topic of this chapter). You need headroom coming into the mix bus (which you have assured in « Stage 2 »), but also coming out of the mix bus. Take a situation where your mix sounds great and is overall very balanced, but as you are comparing the mix to references, it lacks bass. Like, the kind of bass you would get by cranking up the bass knob on a HiFi Amp. That is not really a big deal – I would probably insert a Pultec-style EQ, and boost at 60Hz. A boost like that is hefty in terms of required headroom – it can quickly add 6dB to 8dB of level to the mix bus!

Each processor inserted on the mix bus gives you – of course – handles to get some headroom back. I’m talking about the input and output-controls of a plugin. Back off 1dB on each of those to get some headroom back if you’re getting near the trouble-zone. When all processing is done, and you end up with 3dB of headroom at the end of your mix bus, you’ve done a solid job. More is nice, but what we’re talking about here is the headroom you leave for the mastering engineer to do his thing. In light of 20 years of loudness wars, these guys are happy if you leave them any headroom.

If you make it a habit to shoot for the -3dB to -5dB range going OUT of the mix bus, you will have more space for unexpected events though. The longer you work on a mix, levels will creep up with every new plugin involved. You can avoid this problem if you follow the guidance in this chapter, but most people definitely underestimate the headroom needed when you first set up your mix.

More than one mix bus

Personally, I make a clear distinction between Mix Busand Master Bus, and for good reasons. One of the reasons: working with several mix busses. Without going into detail here, this is something pioneered by mix engineer Michael Brauer on SSL consoles that have several stereo mix busses, like the SSL 6000E/G, 8000G and 9000J/K. Just as a quick example for adding a second mix bus: your track has punch, solid glue and a great low end – the bus compressor and EQ on the mix bus work great, but unfortunately not for the lead vocals, they are too affected and squashed by the bus compressor. What you do is route them around your main mix bus and create a second mix bus. The second mix bus (for the vocals) will of course add some level, has its own signal chain, and the sum of both mix busses feeds the master bus. For that to work, you need a healthy gain structure!

Stage 4: Your Master Bus

OK, the master bus is where you finally mess up your audio to compete in the loudness war, right? I personally always have a brickwall limiter on my master bus, and thats about it. I’m limiting maybe half a dB as a standard, not more. Usually that gives me the RMS / LUFS values I set out to achieve. If I want more (average) level, I either reduce some peaks on individual tracks, or carefully adjust the Mix Bus, but I never do that by slamming the final brickwall limiter. For the final mix pass, I just take the limiter off, and print a WAV (to hand to the mastering engineer in case one is involved – see chapter 12).

HOW LOUD SHOULD MY MASTER BE?

The age of streaming music, these days mainly through Spotify, YouTube and Apple Music has brought a lot of new challenges and opportunities to the audio world. One of them is the goal to give listeners of music streaming services a steady listening level across different genres, with music from more than 6 decades listened to. In other words, if the playlist you’re listening to starts with a 1950s Frank Sinatra-track, then continues with a 2012 EDM-song, you still want both to be at a similar perceived listening level. Luckily there are now very clear LUFS recommendations, and I’m going in detail on this in chapter 12.

3.: Create a playlist with references of songs in a genre similar to the song you’re mixing as we’ve been talking it through in chapter 3

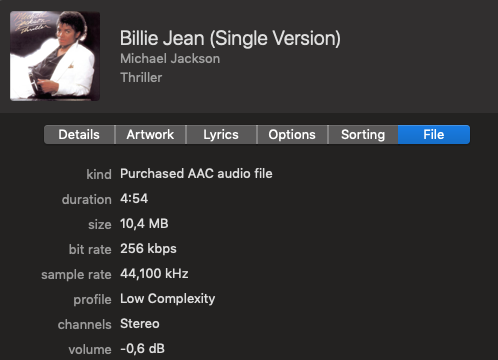

4.: « Get Info » for the song (command + i on your keyboard), chose the « File »-Tab and check the « Volume »-value

5.: Compare these values to the value that your mix shows when you play it in iTunes

If your references sit around – 7,4dB, and your own mix is at – 11,3dB, you’re too loud. If your own mix sits at – 0,4dB, you need to find about 5dB in volume (maybe the Limiter is not making up for the headroom gain). To clarify: the « Volume »-column in the iTunes File-Info tells you what iTunes is doing to the playback level of the song. If it says « – 7,4 », iTunes turns the level down by 7,4dB, because it’s 7,4dB louder than what Apple likes to see. In other words: The lower the « Volume » digit is, the better.

HERE’S WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ITUNES SOUNDCHECK AND MASTERING LEVELS:

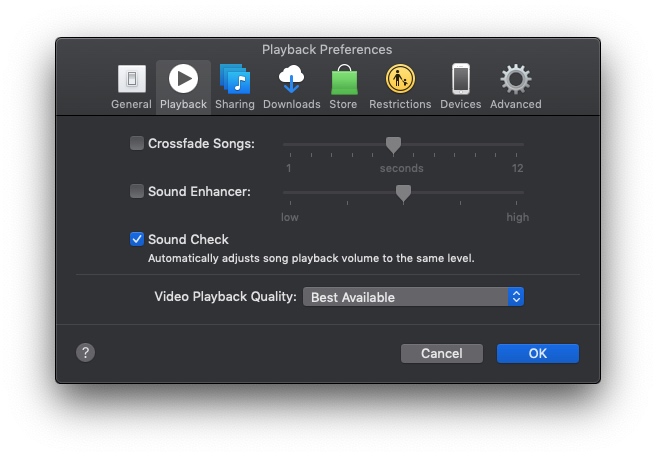

• In iTunes (the app), the « Sound Check »-option that automatically corrects all songs in your library to similar subjective playback-levels does affect the pre- listening in the iTunes Store as well – so no « Loudness- war » happening on iTunes any more really

• All Apple-devices have the « Sound Check »-option

• Levels are not as crazy as they were and differ from genre to genre

SOME INTERESTING EXAMPLES OF LEVELS…

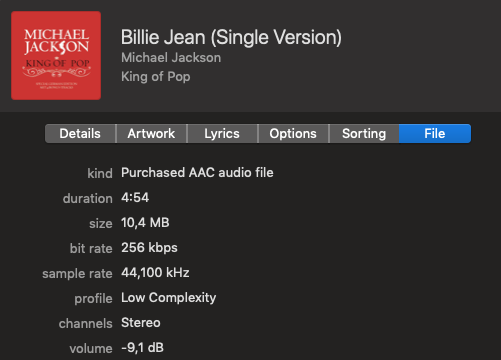

Compare the original album-master of « Billie Jean » with the remastered version:

The transients on the King of Pop’s « Billie Jean » remaster are really squashed, plus the snare reverb is brought up in a very unpleasant way. Sorry, but: I can’t listen to this! Let’s look at another example:

What I’m proposing here is of course not new – mastering engineer Bob Katz has done incredible work in educating audio engineers, and his « K-System » dB- scales are implemented in a number of plugins you should be using to improve your gain staging. The K-System goes beyond leveling, it even includes standardized listening levels. In short, what you can utilize is that iTunes has a very intelligent algorithm that measures RMS, and adjusts all tracks in a way that regardless of what song you’re listening to, they will all appear roughly in the same perceived loudness. I think, they did a good job, and I’m planning to release an album on iTunes with just test-material at different levels to find out exactly what happens. The most important thing to know about this is that when your mix is extremely squashed with high RMS and little headroom, iTunes will turn it down and it will end up lower than other tracks.

If you found this post helpful, check out the YOUR MIX SUCKS Waves Edition. YOUR MIX SUCKS is the complete methodology for the entire mixing process from preparation to delivery. In addition to the technical and artistical side of things, the e-book also deals with the people aspects of mixing audio: From networking to dealing with client feedback. Over the course of 14 chapters the Waves Edition is the ultimate guide and inspiration to mixing music with Waves plugins.